Hakaka pokohiwi me tāhana mahi

Shoulder Anatomy and Function

Your shoulder girdle is wonderfully and perfectly adapted for its function.

You use your shoulder for carrying bags, and children shrug their shoulders as a way of communicating. Our shoulders are made up of bones, joints, muscles, tendons, bursae, nerves, blood vessels that work in harmony to position our hands wherever we want them for getting dressed, cleaning the house, driving, attending to personal hygiene, sporting and leisure activities, and for work.

This video describes the anatomy and terms often used by health care professionals.

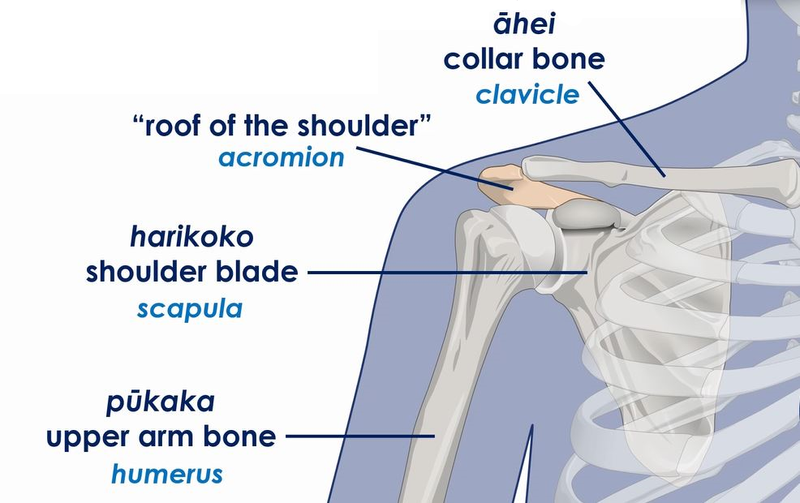

The shoulder joint

Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle). The head of your upper arm bone fits into a rounded socket in your shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. A ring of cartilage called the labrum forms a cup for the ball-like head of the upper arm bone to fit into.

The capsule surrounds the head of the upper arm and the socket of the shoulder blade. A number of small sacks with fluid (bursae) surround the shoulder underneath the deltoid muscle. These sacks cushion and protect the tendons of the rotator cuff.

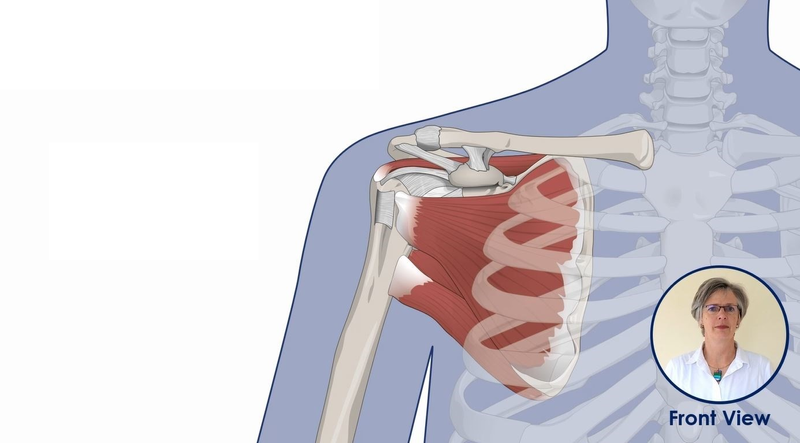

Shoulder muscles

The largest muscle just under the skin is the deltoid muscle, the ‘power’ muscle of the shoulder: it lifts the arm in all different positions. That muscle is supported by the breast muscle (pectoralis major) and the large muscles between the shoulder blade, the trunk, and the shoulder (serratus anterior, trapezius muscles).

The deltoid lies over smaller, deep muscles and tendons, called the rotator cuff. This ‘cuff’ keeps your arm bone centred in your shoulder socket. The muscles come from the shoulder blade and extend into tendons that insert on the head of the upper arm bone. The tendons blend with each other and act like a broad elastic around the head of the bone. They act very quickly, even before you start visibly moving the arm. Their action ensures that the head of the arm bone is perfectly placed against the socket. That keeps the shoulder joint safe, and the movement effective and fit for the specific purpose.

The anatomy of the muscles are perfected to work in unison, allowing them to work in thousands of different coordinated patterns. Our brain can change those coordination patterns at a split-second to protect the shoulder (and body) and to make us most efficient.

To improve and maintain shoulder health, we need movement - of the shoulder girdle itself and of the whole body.