Te whaihaka ki te mamae

Pain Management

Living with shoulder pain – or any pain – can be stressful. It can interfere with our daily life (such as when getting dressed), at work, our hobbies, any physical activity, and sports. The pain may interfere with sleep and make us feel depressed, anxious or hopeless. Some people with shoulder pain can feel lonely, left out and misunderstood when they can’t meet up with friends or whānau (family) or do things with them as usual. We may try to avoid movements that worsen the pain or not to get re-injured. In turn, avoiding movement may make us feel miserable and unwell.

The good news is that there are things we can do to enjoy life and reach goals despite shoulder pain. People respond differently to treatments. What helps you depends on many things, including your lifestyle - your daily tasks, work, hobbies, sports and exercise - and your beliefs.

In this section we discuss why we feel pain, treatment options and what you can do yourself for your shoulder pain, and helpful exercises you might be able to start with.

Why Do We Feel Pain?

Shoulder pain may come on suddenly (as in an accident or with an injury) or develop gradually. Gradual onset pain may be due to either repetitive movements (as in some occupations, or with sports training), unaccustomed movements, or doing too little movement.

As indicated in Common conditions, injuries may be due to fractures, dislocations or muscle-tendon tears; these can usually be identified. With persistent pain it is often difficult to establish exactly the precise anatomical structure which is causing the pain.

The good news is that we can do something for the pain even when we do not know exactly what anatomical structure is causing the pain. It is important to understand why we are feeling pain, what pain means, and most of all, how we can change and control pain. |

Pain as danger signals

Pain is a sensation and we feel pain to protect our body.

If we sprain a joint or muscle, there may be swelling and we feel pain. We may protect the joint or muscle by not using it as we normally do. The swelling brings chemicals and cells via the bloodstream to clean up the injured area and to start the repair process. That is normal inflammation, which is an important part of the repair process. Over a few days, the pain or swelling decreases. We return to our normal activities, progressively move the jont more or add more weight. Movement and loading is important to guide recovery in the joint or muscle tissues.

Shoulder injuries are no different. When we hurt the shoulder, we may avoid certain movements for a while. As the pain gets better, we gradually return to movement and usual activities.

Sometimes the pain persists despite the likelihood that the injury has healed. We call that ‘persistent’ pain. Alternatively, we may find that the pain comes and goes, sometimes for no obvious reason. We call that ‘recurring pain’.

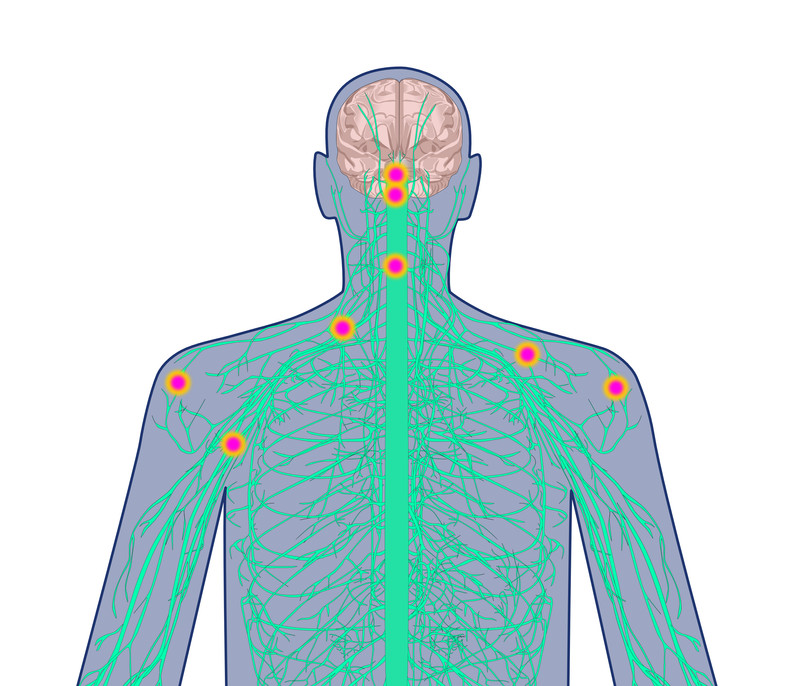

The brain as a super-computer

The brain is like a super-computer constantly monitoring messages from all parts of the body. When we get injured, ‘danger’ messages are sent to the brain via our nervous system. The brain constantly processes all the messages that it receives.

If the messages are considered to be ‘danger’, we feel pain. The brain sends messages back to the shoulder. We become reluctant to move the shoulder, which is a good thing when we have a fracture or dislocation! The brain processes are protective. In most cases, we resume movement over time. But if the protection continues for too long, we lose muscle control and strength. Thus, starting with movement as soon as is safe is important.

Interesting about the brain and our pain experience:

If the brain prioritises other messages from the body, those 'other' messages over-ride the 'danger' message. The brain then analyses the situation as not being ‘dangerous’. That may happen when we focus on something we really enjoy – perhaps being part of a waka ama team in a competition, or having a good conversation during a walk with friends - that we don’t even notice that we have pain in the shoulder.

On the other hand, sometimes a small ‘danger’ message can be processed as being ‘very dangerous’. That occurs when a small injury – or just a small movement – leads to excessive pain. That can happen when we are stressed for other reasons, are afraid of another injury based on our experience, or are tired or run down. That can also happen if we have pain elsewhere in the body, such as back or neck pain, or hip pain, in addition to the shoulder pain. We talk about that as 'increased sensitisation' of the nervous system.

In a sense, the nervous system can change how sensitive it is. It can be in ‘high alert’ or ‘low alert’. During ‘high alert’, we may feel more pain, or get pain sooner (increased sensitisation). In ‘low alert’ we can tolerate sensible and appropriate movement and activities.

The goal is thus to keep our whole nervous system at ‘low alert’ level. In a sense, we want to ‘de-sensitise’ or ‘calm down’ the nervous system as part of taking care of the shoulder and of our whole body. We can 'train the brain' to regulate the alert’s alarm system. |

Check out these videos

Tame the Beast - It's time to rethink persistent pain

Understanding Pain: Brainman chooses

Understanding pain in less than 5 minutes, and what to do about it!

Download this pdf booklet: Understanding Persistent Pain, Tasmanian Department of Health & Human Services (June 2024)

Page and links checked by Gisela Sole, 25th September 2025.